Internet Echo Chambers and the Rise of Ignorance

By: Dmitry Pleshkov

We live in an age where almost all of humanity’s recorded knowledge is readily available through the Internet. What would have amounted to searching several libraries for days about seventy years ago is now a simple query into a search engine. The answers to most scientific questions are at the tip of your fingers. And yet, somehow, we are seeing a sudden rise of outrageous, ignorant, unscientific beliefs despite the facts to disprove them being mere seconds away. Why?

The principle of echo chambers

What social echo chambers do, in essence, is continuously reinforce certain beliefs and opinions. As part of our tribal instinct, we as humans naturally prefer to keep company with those who are similar to us — be it their appearance, interests, or opinions — it’s unlikely you’d make very good friends with someone entirely different from you. It is upon this principle that echo chambers form: as one surrounds themselves with people with similar opinions, those opinions tend to not be argued against as much as they are argued for. Suppose, for example, that I believe that the earth is flat and surround myself almost exclusively with fellow flat-earthers. The number of people I will have arguing with me against my belief will be far less than the number of people I will have arguing for my belief. Thus, I’ll remain comfortable with my belief that the earth is flat and will be far less likely to change this view if someone does decide to argue with me.

Social media encourages the creation of echo chambers

Fortunately, ignorant and outrageous beliefs like flat-earthism remain a minority in our modern society, for the most part. Without the Internet, I, as a flat earther, would have a hard time finding someone who shares the same belief as I, as almost everyone knows the earth is round and would ridicule me when I tell them I’m a flat-earther. Simply put, the desire to conform to social norms would prevent my ignorant belief from being reinforced further.

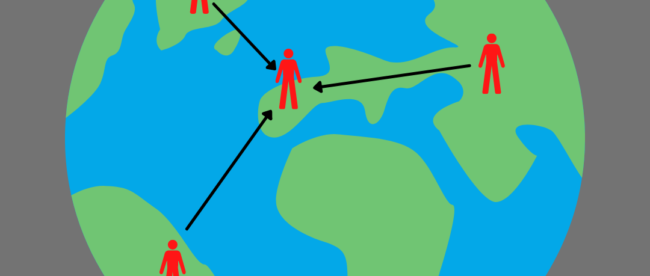

Without the internet, it is much harder for someone like a flat-earther to find another fellow flat-earther as the vast majority of people aren’t flat-earthers.

The presence of the Internet and social media changes this. As most social networks generate revenue from ads and data collection, it is in their interest to show you content you’re interested in as you’re more likely to interact with that content and thus spend more time on the network. Various posts are typically tied together with a hashtag and the ability to follow certain accounts, join private groups, and create group chats makes the perfect recipe for an echo chamber.

Suppose — again, hypothetically speaking — that I as a flat earther suddenly gain access to a social network like Facebook. Having a desire to find people who also believe our earth is flat, I search for something along the lines of “#flatearth”. Within a couple of clicks, I am able to find posts and other people that share my belief. A couple clicks more, and I’m following them and joining groups titled something like “Flat Earthers”. Soon, my feed is filled with posts and people sharing content that, factual or not, supports my irrational view. Instead of being ridiculed by the first two dozen people, I talk to in real life, on social media I’m easily able to find a handful of people who think alike. Thus, instead of my belief being discredited from the start, it is accepted and reinforced.

Having social media and the internet, a flat-earther can easily find other fellow flat-earthers around the world. The irony in this picture is intentional.

Ignorance is bliss

The more time I spend engaging in my flat-earther social media group, the harder it is for actual concrete facts and reasoning to change my belief. When I have fifty other flat-earthers I’ve met through social media echoing my beliefs and supporting me versus a single person arguing with me and likely insulting my intelligence, I’m more inclined to remain a flat-earther than to listen to that one person. The sense of community and belonging that being in a flat-earther echo chamber brings outweighs the sense of being right in the majority of the population that would regard the belief in a round earth as being normal and thus won’t celebrate it. People like to feel special. Believing the earth is round doesn’t make someone special. Concrete, real scientific evidence is unlikely to change my belief once I’m part of such a community as I will simply value being in my group more than being right and will ignore any contradictory evidence one presents to me — while at the same time cherishing any evidence supporting my belief. This process is often referred to as cognitive dissonance.

Effect of echo chambers on society

An anti-vaccine rally in New York

Flat-earthism is used in this article as a relatively harmless example of an irrational belief that can be reinforced by being in a social media echo chamber. The reality is that plenty of such beliefs are becoming more and more accepted today due to this phenomenon, including but not limited to anti-science sentiments like denial of climate change or denial of vaccine efficacy, and conspiracy theories like Qanon. The anti-vaccination movement, in particular, has been responsible for encouraging a resurgence of illnesses like measles and polio that previously came close to being eradicated and prolonging the COVID-19 pandemic that we’re currently in.

Another notable example of this phenomenon having real-life consequences is the January 6th riot at the US Capitol — believing the 2020 presidential election was a fraud and organized through social media, hundreds of people broke into the Capitol, forcing the Congress to evacuate.

One solution to this is passing legislation forcing social media companies to take responsibility and take steps to reduce misinformation being spread on their platform. The obvious problem with this is that such legislation would likely be unconstitutional — after all, free speech is free speech, our government can’t take away people’s right to spread misinformation.

While such restrictive laws on speech might not pass in our country, other laws mitigating the effects of the problem rather than the root are definitely passable. One notable example is our president Joe Biden’s vaccination mandate for businesses larger than 100 people, requiring people to either get vaccinated or be tested regularly for COVID-19. The anti-vaccination movement is a notable example of how an ignorant belief can gain traction and become a real societal problem — nearly all COVID deaths in our nation are among the unvaccinated portion of the population, and in most cases requiring intensive care are also among the unvaccinated.

All in all, here are some things you can do to prevent yourself from being a part of this problem:

- Fact-check information. Even if something stated is a fact, it may be out of its appropriate context. Statistics are easy to cherry-pick to support a certain point of view.

- Recognize that social media algorithms attempt to show you the information you engage with. It is easy to become a part of an echo chamber simply by following people sharing similar political opinions as you. Usually, this isn’t problematic unless such opinions are regarded as extreme by the majority.

- Recognize that some accounts you engage with might be fake. It is fairly easy to create a convincing fake account on most social media sites, not to mention that there is a great political interest in spreading misinformation on the Internet.

Sources:

https://cdn.discordapp.com/attachments/512757801680896011/888644681766944798/socialcircle.png (image by Dmitry Pleshkov)

https://cdn.discordapp.com/attachments/512757801680896011/888645825666891776/socialcircle_1.png (image by Dmitry Pleshkov)

https://live-production.wcms.abc-cdn.net.au/2b7f50955c3095d88ba418228846c5f4?impolicy=wcms_crop_resize&cropH=632&cropW=1130&xPos=805&yPos=225&width=862&height=485 (image borrowed from Australian broadcast corporation)