A love letter to fan content

The truth about transformative literature’s trickiest genre.

By Niko Adams

Everyone has read fanfiction.

The term fan has become something of a phenomenon in the last few decades. The word ‘fandom’ was only recently coined to describe the attention that media receives in our age of high-speed communication and globalized unity. It has brought along with it a sudden influx of vocabulary and new connotations to older words. And along with this sudden change in consumption of content has come a dramatic attitude shift towards an entire genre of contemporary art, literature, and film.

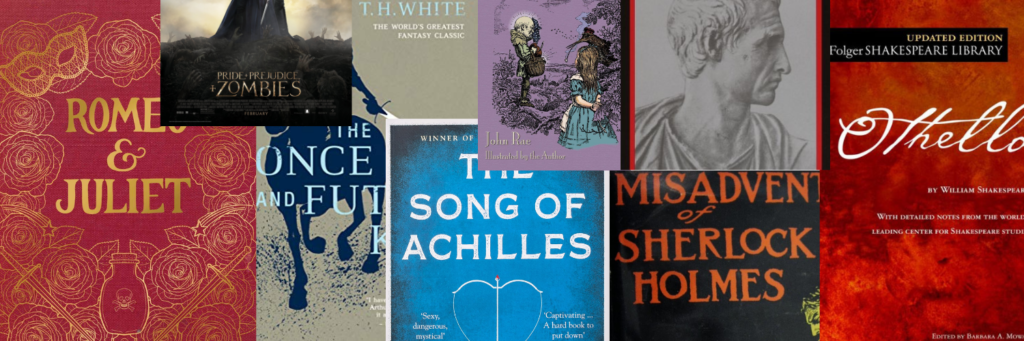

You have read fanfiction. Though perhaps not fanfiction in the modern sense — the kind that is published free of charge on the internet— but rather the kind that has created entire college courses, documentaries, and spawned inspired novels and movies alike. Romeo and Juliet, Othello, Inferno, The Aeneid, The Three Musketeers, and The Once and Future King being some of the most well-regarded and famous among them.

You might recognize these titles as classics, or literary masterpieces. Some are works of art that feature in galleries— like pre-internet sculpture busts of Star Trek characters that have famously won awards. But they all share one thing in common with the works you can find on DeviantArt, AO3, and FFnet today: they’re all fan content. Made for free. And made for ever-growing demand.

Fan content is no stranger to the mainstream, either. The highly popular (and also somewhat controversial) Twilight series was the source work for 50 Shades of Grey, and After originally began as a One Direction fanfic on the internet where it gained hundreds of millions of views before its official publication and its transformation into a blockbuster movie series.

Although these modern works do not necessarily have favorable beginnings, their impact on culture and their influence on future media is irrefutable. Twilight changed vampire fiction forever (for better or for worse), and After’s popularity started an incredibly important discussion on RPF (real person fiction) and the rights of celebrities to their image in popular media. Even the hit CW show Supernatural resulted in a federal court case regarding intellectual property in fan works. But how and why did they fall from grace?

The change in perception of fanfiction began in the late 20th century, when Star Trek and Sherlock Holmes dominated the modern fan content scene. Pre-internet fan content was published in monthly magazines, mailed to your doorstep on demand, and tacked onto library billboards by local groups. The large involvement of women— particularly housewives and teenage girls — in creating these works, organizing the first cons (conventions), and actor meet-and-greets, has most certainly influenced the way we see transformative works today. “Fanfiction” is culturally synonymous with “fangirl” and all the negative connotations attached to the term. The Song of Achilles is the same form of contemporary writing that Pride & Prejudice and Zombies is, yet their welcome into the world has been heavily influenced by perceptions of slash (LGBTQ+) romance, the demographics of their authors, and the literature world’s stance on the reinterpretation of classic works.

In the past, reinterpretations of timeless stories, and reinventing tales for the modern audience was a widely-accepted form of literature. And notably, the authors of these stories were mostly wealthy, white, and male. The rise of the internet has given the world of writers a level playing field, where an audience for works is largely accessible, and the free-rein of the web takes away the obstacle of race and gender in the quest for public posting. But this accessibility does not easily translate to hard-cover copies and big name-publishing opportunities, where we still see a disproportionate amount of heterosexual and white authors on every shelf regardless of genre.

It is almost as if, despite their quality, the general consensus regarding fanfiction as a contemporary form of literature is that if it started on the internet it should stay there. And although the historical proof says otherwise, it is a product of many social expectations and pressures that art forms reinvented and promoted by women should find themselves minimized at the expense of their audience. Perhaps the world will begin to see fan content favorably again— just as it once revered rewrites of the Bible, famous poems, and legendary tales. But truly, only time will tell.